A couple days ago, I mentioned that we’re hosting Joel Jamieson’s new Certified Conditioning Coach course at our facility on April 2nd and 3rd. In response to that post I received a bunch of notes from people either expressing an interest in taking the course, or telling me how great it was when they took it previously.

If you’re interested in taking the course, register ASAP. We’re limiting the course to ~40 attendees and have already sold over half the seats. You can get more information and register at the link below.

Reserve your seat here >> Certified Conditioning Coach

Given the interest in energy system development my last post sparked, I thought it would be an opportune time to repost a video I’ve shown a few times of a presentation Joel gave on the topic. This is a GREAT presentation, and one of the best free resources available. Check it out below!

A few years ago when I first came across this presentation from Joel Jamieson, it caused me to rethink a lot of what I thought I knew about “conditioning”. Since that time, I’ve read (and re-read) his two books, seen him speak a few times, and even spoke alongside him when the two of us did a one day seminar (where Optimizing Movement was filmed).

Ultimate MMA Conditioning is a must-read for anyone that trains athletes in any sport

Needless to say, I think this information is incredibly valuable; it’s had a profound impact on the way that I write my programs.

Even in rereading my comments about the video below, I know that my perspective on energy systems work has changed considerably over the last 4 years, especially as it pertains to redeveloping aerobic qualities in hockey players (and all athletes in general) in the early off-season. We’re using methods now that I would have never thought to use in 2011, and the foundation for a lot of that change was built on this video.

Enjoy! And if you want to share any of the conditioning methods you’re using or have any questions, please post them in the comments section below.

A New Perspective on Energy Systems

I hope you’re all enjoying your day off (if you got one). Endeavor Sports Performance typically shuts down for Memorial Day, but Matt, David, and I are leaving Thursday night to head up to Boston for the Hockey Symposium, so we have to open up today to make sure all of our athletes can get their sessions in before we go. Just another day in the office! (I’m pretending that today isn’t the first day that it hasn’t precipitated since last November).

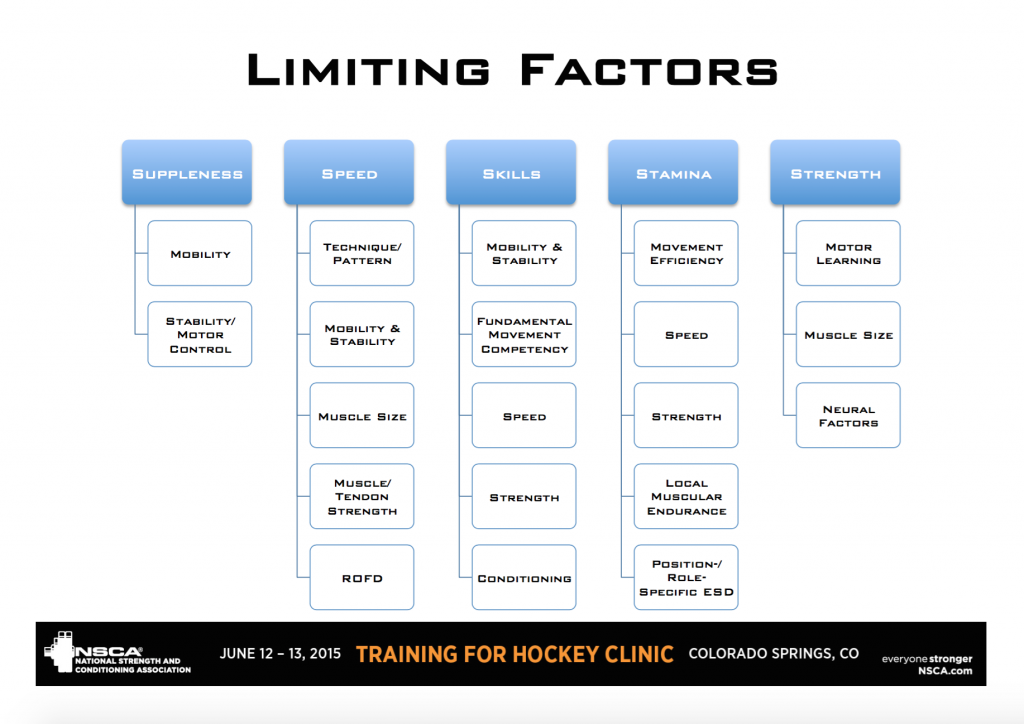

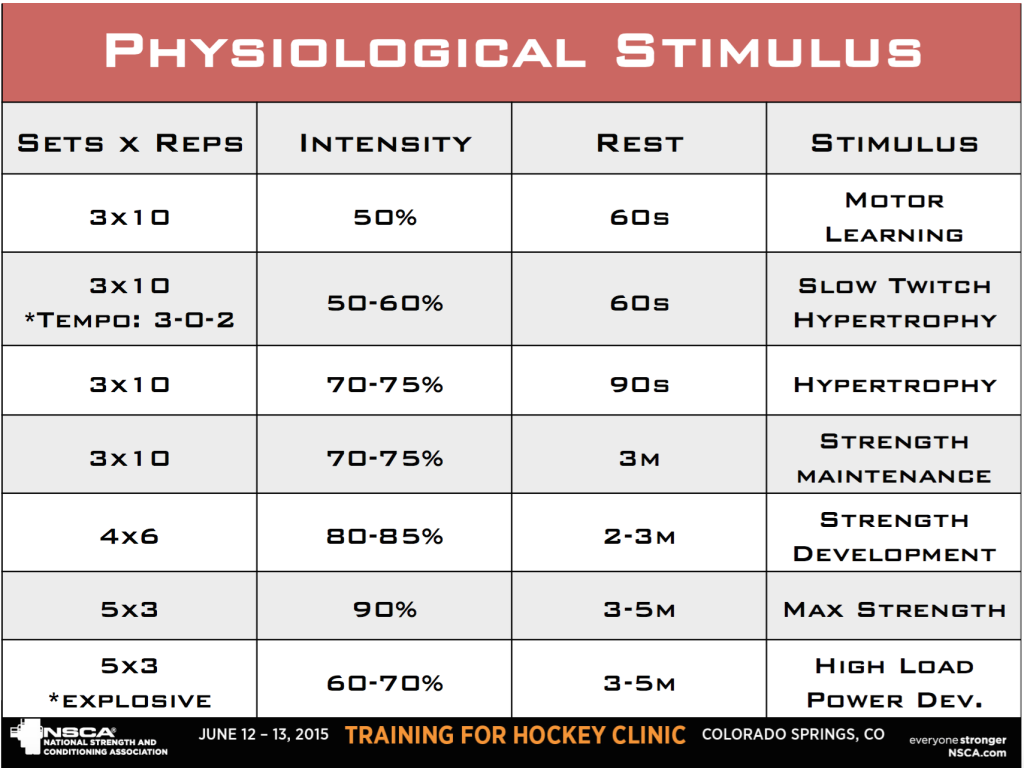

Rather than spending the day outside enjoying the sun and BBQing, I thought you’d be more interested in watching a great presentation on energy systems development from Joel Jamieson, who’s a really bright guy. Joel primarily trains MMA fighters out of his facility in Seattle, WA, but he also has experience with football and soccer players. More importantly, and you’ll get this quickly from watching his presentation, his training philosophy is science-based. While I don’t think that every line on a training program needs to have a citation next to it, I think using quality research as a backing for your training philosophies ensures that you understand the underlying principles of athletic development, which can be effectively applied to any sport (in a sport- and athlete-relevant manner).

This video is from a presentation Joel gave at the Central Virginia Sports Performance Seminar at the University of Richmond in Virginia, and he includes a download link for the power point slides so you can follow along. Click the link below and watch the video now (it’s completely free and doesn’t require registering for anything):

Click Here to Watch >> A New Perspective on Energy Systems

I finished watching the video late last week and left with a few good research resources to look into and an augmented understanding of energy metabolism and physiology. I can’t help but feel that some of his words will be grossly misinterpreted though.

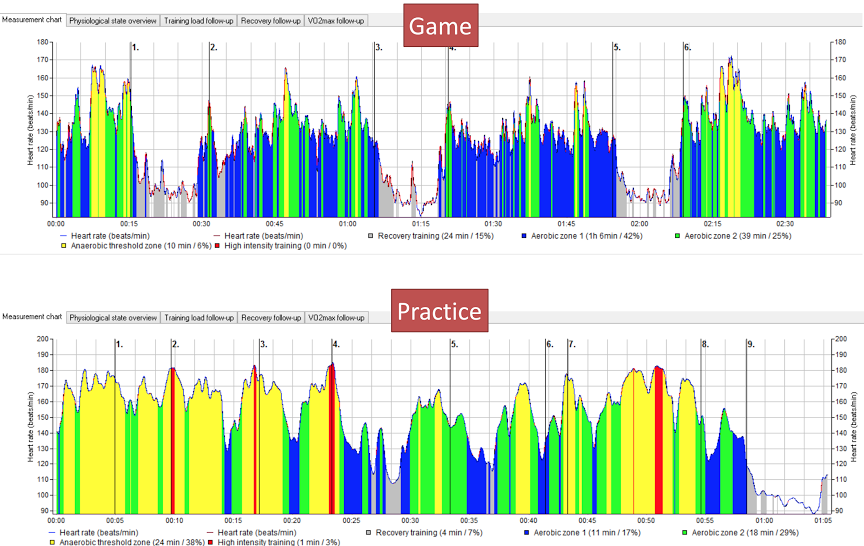

One thing that stood out to me as extremely hockey conditioning relevant is the large degree to which the aerobic system contributes to repeat sprint performance with incomplete recovery. Using running as a model, Joel presented that the energy delivery for 200m (~22s) and 400m(~49s) sprints were 29% and 43% aerobic, respectively. In other words, in the time equivalent of an average hockey shift, roughly 1/3-1/2 of the energy provided is aerobic, and this is likely to increase with incomplete recovery between bouts (e.g. as shifts progress within a period).

In my opinion, Joel’s presentation offers more accurate explanatory power than it does a drastic change in the way we condition for hockey. The major take home message is that you need to understand the demands of the sport and prepare accordingly. I think people see something like “50% of energy is from anaerobic sources and 50% is from aerobic sources” and think “50% of my training should be sprint repeats and 50% should be continuous aerobic work.” In reality, all this is saying is that the sprint repeats will eventually be developing aerobic systems in addition to the know anaerobic benefits.

Primarily Aerobic? Anaerobic? Does it matter?

This is one of the reasons why I think it’s more important to have an in-depth understanding of the work:rest ratios and overall work intensities of the game than it is to understand the underlying physiological mechanisms driving them. As an overly simplified example, if hockey includes, on average, about a 40s shift of which about 20s is spent at all out intensities every 3 minutes, and we use some similar work intervals and work to rest ratios to create a slight overload on the involved metabolic systems, does us realizing that more of the on-ice energy AND off-ice training energy is coming from aerobic metabolism than we previously thought change the way we train? I’m not sure it does. I’m certainly not implying that I disagree with anything Joel said in his presentation, and I agree that certain athletes will need a greater emphasis on certain qualities based on their athletic profiles, but I think some people over-emphasize the physiological explanations and under-emphasize the much more obvious and intuitive game demands. What do you think? Check out the video and post your comments below!

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

HockeyTransformation.com

OptimizingMovement.com

UltimateHockeyTraining.com

Please enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Athletic Development and Hockey Training Newsletter!

Get Optimizing Movement Now!

“…one of the best DVDs I’ve ever watched”

“A must for anyone interested in coaching and performance!”