Today’s Thursday Throwback takes us back to 2011 and provides an inside look at what used to be a very popular supplement. Aside from the specific supplement referenced here, there are two big takeaways from this post that you should apply to ALL supplement choices:

1) It’s important to familiarize yourself with the brand. Because the supplement is completely unregulated by the FDA, companies can put whatever they want into their bottles. Simply, there’s no guarantee that what they claim the supplement contains (e.g. creatine) actually has that ingredient in the quantities they’re advertising. Some brands have gone through the process of becoming “NSF Certified for Sport” or have been certified by “Informed Choice”, which should give you a higher level of confidence that the supplement contains what it’s supposed to. I strongly discourage our athletes from going to supplement/grocery stores to by supplements. It’s unlikely a high quality brand is even carried at the store and a lot of the sales people at the more popular stores are dangerously under-informed.

2) A lot of times less is more. There are TONS of supplements, and supplement ingredients, out there, but the overwhelming majority have no scientific support that they actually work. A lot of times popular supplements contain a few inexpensive ingredients that do work, and a ton of “extra stuff” that doesn’t, and you end up paying a premium for inflated marketing campaigns and colorful wrappers instead of a higher quality ingredient. Knowing which supplements actually work can be tough to stay on top of, which is why I frequently refer back to this: Examine.com Supplement Goals Reference Guide. It’s nice to have an unbiased, comprehensive look at every supplement so you can quickly see if there’s research supporting it’s effectiveness.

The most informative, honest, unbiased look at supplementation, ever.

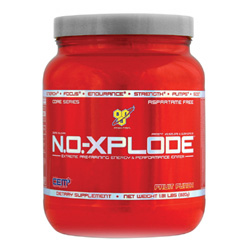

NO XPLODE Exposed

A couple years ago I wrote a supplement review that we never took to print. There was a considerable conflict of interest because the nature of the article could negatively impact sales of one of the site’s top sellers. To be honest, they handled it really well, apologizing to me and noting that it wouldn’t be good for their reputation with the company. I understood and still do; relationships are everything in business. With that said, I think the wide-spread use of this supplement is ludicrous and potentially dangerous. A deeper look inside:

NO XPLODE-A Look Inside

Assuming you don’t have an NO2 label in front of you (hopefully you don’t), let’s take a look at the nutrition facts and some of the other ingredients to see if we can pick out the ingredients out that are driving their marketing claims.

Calories: 25

Fat: 0 g

Carbohydrate: 6 g

Sugar: 0 g

Protein: 0 g

Vitamin B6: 25 mg

Vitamin B9: 400 mcg

Vitamin B12: 120 mcg

Calcium: 75 mg

Phosphorous: 535 mg

Magnesium: 360 mg

Sodium: 235 mg

Potassium: 75mg

Ingredients (get ready!):

In addition to the components listed above, N.O.-XPLODE contains N.O.-Xplode™’s Proprietary Blend, which consists of: L-Arginine AKG, L-Citrulline Malate, RC-NOS™ (Rutacarpine 95%), L-Citrulline AKG, L-Histidine AKG, NAD (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide), Gynostemma Pentaphyllum (Leaves & Stem) (Gypenosides 95%), Modified Glucose Polymers (Maltodextrin), Di-Creatine Malate, Trimethylglycine, Creatine Ethyl Ester -Beta-Alanine Dual Action Composite (CarnoSyn®), Sodium Bicarbonate, Sodium Creatine Phosphate Matrix, Creatinol-O-Phosphate-Malic Acid Interfusion, Glycocyamine, Guanidino Proplonic Acid, Cinnulin PF® (Aqueous Cinnamon Extract) (Bark), Ketoisocaproate Potassium, Creatine ABB (Creatine Alpha-Amino-N-Butyrate), L-Tyrosine, Taurine, Glucuronolactone, Methylxanthine (Caffeine), L-Tyrosine AKG, MCT’s (Medium Chain Triglycerides)[Coconut], Common Periwinkle Vinpocetine 99%, Vincamine 99%, Vinburnine 99% (Whole Plant), Di-Calcium Phosphate, Di-Potassium Phosphate, Di-Sodium Phosphate, Potassium Glycerophosphate, Magnesium Glycerophosphate, Glycerol Stearate.

Other ingredients include: Citric Acid, Natural & Artificial Flavors, Calcium Silicate, Potassium Citrate, Sucralose(Splenda®), Acesulfame-K, FD&C Red #40, And FD&C Blue #1 (These are mostly just preservatives, sweeteners, and colors).

I’ll be honest. I’m far from a nutrition and supplement scientist. There are some people that could quote strengths and weaknesses of research on most of the above ingredients-I’m not one of them. I do, however, stay current on research demonstrating consistent effectiveness of specific supplements. In that light, there are a few things that really stand out to me when looking at the excessive laundry list of ingredients in NO XPLODE.

If you scan through the ingredients you’ll see creatine, beta-alanine, and caffeine. All of these have been shown to be safe and effective compared to a placebo in eliciting greater increases in muscular size and strength (creatine), and work capacity and endurance (beta-alanine and caffeine), and there is some more recent work suggesting that caffeine taken in pretty high doses may be effective in increasing maximal strength via an increased neural drive mechanism.

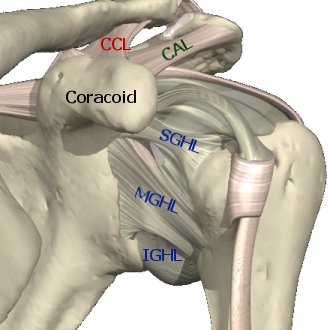

The “get a big pump” claim of NO supplements insinuates greater increases in muscle mass and strength as a result of the NO2 precursor l-arginine (an amino acid), which is largely unsupported. Arginine MAY have some benefits in patients with heart problems, but only in higher doses (in the realm of 10-15 g) known to cause almost inevitable gastrointestinal distress. In short, there is no research-supported reason to think that NO2 will increase the size and strength of your muscles. Furthermore, it’d be fair to say that the overwhelming majority of the long list of ingredients in these supplements are worthless for the purposes of improving training outcomes in athletes.

Why All The Hype?

So why all the positive reports and borderline evangelical support for NO2 supplements? There are a couple reasons. For starters, this supplement has received a ton of attention from teenagers. Because it increases your heart rate as a result of the caffeine, those new to training love it. They feel more energized. They also get significantly bigger and stronger. Being logical thinkers, the conclusion is that N.O.-XPLODE gives you the energy you need to train harder to get bigger and stronger. Makes sense, but isn’t necessarily accurate. As I’ve written about before, EVERYTHING works for inexperienced lifters. In fact, I’m fully confident that front planks would increase maximum squat and bench press strength in inexperienced lifters. No matter what teenagers do, they’ll get bigger and stronger. The added rush from a supplement isn’t the cause of these improvements!

“Take NO-XPLODE! I started taking it two weeks ago when I started lifting for the first time ever and it totally worked!” – Typical Well-Intentioned, But Completely Ignorant Teenager

As I’ve mentioned in the past, my stance on supplements is simple. It needs to work (research-supported). It needs to be safe. And, ideally, it should be pretty cheap. NO2 supplements miss the mark on at least the first of my qualifiers, and probably the second. For those that swear by its effectiveness, I won’t disagree that you may get results from it, but it’s not from the nitric oxide components or precursors. Short of duct tape and a soldering iron, they’ve put just about every ingredient known to man inside N.O.-XPLODE. This includes creatine and beta-alanine, which do receive scientific support with regards to increasing muscular size and strength, especially if taken together, and caffeine, which is known to increase energy and focus. With supplements, like food, the less ingredients, the better. Stick with stuff that’s been shown to work and be safe. If there’s a long list of ingredients you don’t understand, don’t take it, regardless of what the high school kid working at GNC tells you.

I think we all need to be more cautious about what we’re allowing teenagers to put into their bodies. It seems that real food has become a minority component of today’s young athlete’s diet. Further, I think we need to take a step back and reanalyze other aspects of their lives if they can’t get a good workout in without loading up on artificial stimulants!

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

HockeyTransformation.com

OptimizingMovement.com

UltimateHockeyTraining.com

P.S. Never waste money on ineffective supplements again >> Examine.com Supplement Goals Reference Guide

Please enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Athletic Development and Hockey Training Newsletter!

Get Ultimate Hockey Transformation Now!

Year-round age-specific hockey training programs complete with a comprehensive instructional video database!

Get access to your game-changing program now >> Ultimate Hockey Transformation

“Kevin Neeld is one of the top 5-6 strength and conditioning coaches in the ice hockey world.”

– Mike Boyle, Head S&C Coach, US Women’s Olympic Team

“…if you want to be the best, Kevin is the one you have to train with”

– Brijesh Patel, Head S&C Coach, Quinnipiac University