Today’s Thursday Throwback features an important article that I originally wrote back in 2010. The concept of Michael Boyle and Gray Cook’s “Joint by Joint Approach” discussed below is the single most effective way to communicate to clients/athletes how a limitation at one joint or segment can influence function or pain in a different area of the body.

This was one of the major movement concepts I discuss in my DVD Optimizing Movement, and is one of the first things I teach to new interns and employees. Simply, this is a great topic for everyone involved in sports, from rehab professionals down to athletes. Enjoy, and if you find the article beneficial, please share it on Facebook, Twitter, etc.

The Mobility-Stability Continuum

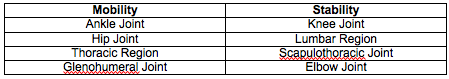

Over the last several years, Michael Boyle and Gray Cook’s “Joint-by-Joint Approach to Training” has changed the way the sports performance world looks at athletic development. Starting from the ground up, the joint-by-joint system outlines that the body has joints alternating in emphasis on whether they need mobility or stability to maximize function. The chart below provides more specific details on which joints need mobility and which need stability. You’ll notice that if you read it from left to right, the joints progress from the ground up within the body: ankle -> knee -> hip -> lumbar (low back) -> thoracic (upper back) -> scapulothoracic (shoulder blades) -> glenohumeral (shoulder joint) -> elbow).

This breakdown helps us understand the mechanism underlying a lot of common injuries. To be overly simplistic, if a joint in the mobility column has sub-optimal mobility (or range of motion), an adjacent joint will need to “fill in the gap” by providing the additional range of motion. Usually this “compensatory movement” occurs at the next joint up. Following this idea, you can refer back to the table and see that mobility restrictions in the left column lead to compensatory movements (and consequent injuries) to the joints in the right column.

For example, if your ankle lacks mobility (especially in the transverse plane), you’ll get it from your knee. This compensation will almost inevitably result in some sort of pain/injury. More specific to hockey player, if your hip lacks mobility, you’ll get it from your lumbar spine, which will eventually lead to back pain. You can see how this joint-by-joint approach creates a paradigm that explains many athletic injuries.

While I’m sure this wasn’t the original intention of either Coach Boyle or Gray Cook, this idea has been interpreted in a black and white fashion: Joints either need mobility or they need stability.

←————————————————————————————————————-→

Mobility Stability

Let’s take a look at the lumbar spine. Each segment of the lumbar spine has about 2-4 degrees of rotation range of motion, for a total of about 13 degrees total rotational capacity. In contrast, the thoracic spine has in excess of 70 degrees (and so do the hips: about 30-50 degrees in both internal and external rotation). From this viewpoint, it’s obvious that we should be emphasizing rotation through the hips and thoracic spine and NOT through the lumbar spine. This fits well in the mobility/stability table above. Failure to do so results in excess rotation through the lumbar spine, which can cause a host of disc and spine issues.

With that said, it’s important to note that we still NEED that 13 degrees of rotation range of motion in the lumbar spine and should use it. We don’t want to force motion past the end range of the joint, but using the allowable motion is absolutely essential to efficient movement. In this example, we want to “cue” movement from the thoracic spine and hips, but we shouldn’t be preaching NO movement at all through the lumbar spine. As Stuart McGill has mentioned, we just don’t want to push that joint (the lumbar spine) THROUGH end range.

Coming back to the continuum, understand that even joints that necessitate a high level of mobility (e.g. the glenohumeral or “shoulder” joint) absolutely need some requisite stability. The same is true for the ankle. In both cases, ligament damage due to injury creates an increase in joint laxity, which by definition improves mobility. However, this mobility comes at the expense of NECESSARY structural stability and increases the risk of subsequent injury to that joint (one example of why previous injury is the best predictor of future injury). In reality, these joints probably don’t belong in columns as much as a continuum as displayed below.

Mobility Stability

When we think of maximizing human performance, we can never think in black and white terms. Each joint needs a specific balance of mobility and stability. If you take only one thing from this discussion, it should be that the body functions as a cohesive unit, meaning limitations in one area will absolutely affect (usually negatively) both adjacent areas and areas further up/down an anatomical pathway. This is just one more reason why isolation training is moronic.

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

OptimizingMovement.com

HockeyTransformation.com

UltimateHockeyTraining.com

P.S. The foundation for maximum athletic performance is built on Optimizing Movement

Please enter your first name and email below to sign up for my FREE Performance Training Newsletter!

Get Optimizing Movement Now!

“…one of the best DVDs I’ve ever watched”

“A must for anyone interested in coaching and performance!”